Recently, my teamlead agile methods pointed me to an interesting corelation. After a discussion we concluded with a really mind-boggling observation. A settled organization facing change will increase productivity when reducing staff headcount – in other words: “Reducing staff leads to higher productivity”.

Bang! But let me explain. For software development tracking and planing purpose we use JIRA – so we’re able to track the amount of created and closed software development related tasks quite easily. The headcount in software development, product management and UX/design can be obtained easily by – counting (we actually asked our HR department for support).

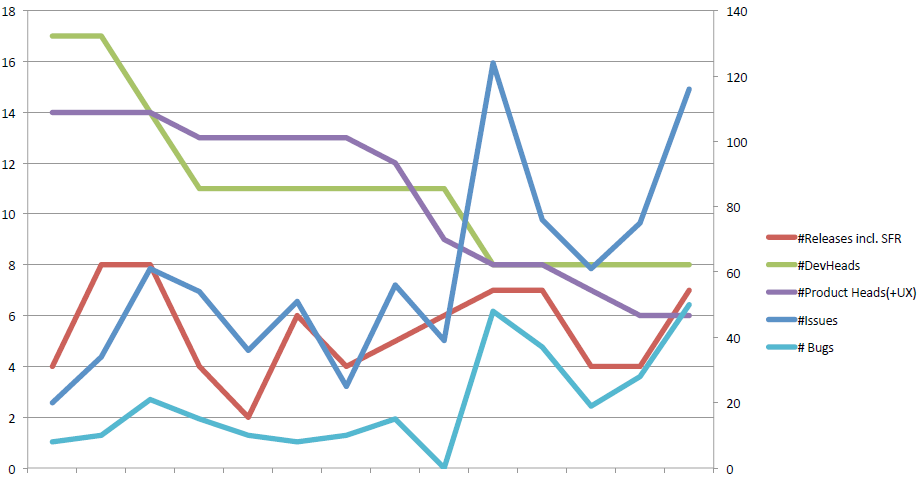

In our case we ended with this curve – impressively proving Brooks’s law.

The graph shows a period from June 2013 (left) to July 2014 (right) and focuses only on one of our products at the time.

Green shows the number of software developers working on the product. Purple shows the number of product and UX/design people involved. The two curves are declining.

Red shows the amount of releases done in the period.The curve is trending towards a stable, flat curve.

Blue shows the amount of tickets closed and turquoise the amount of bugs closed. The two curves are decreasing trending towards a way higher plateau.

What happened? In June 2013 time frame we had a whole architecture team and quite some software developers organized in three teams working on our product. Around this point in time uncertainty hit the organization due to rumors of to-be-expected acquisition of our whole company. Uncertainty translates often to people leaving the organization. This can clearly be seen in the middle of the graphic. Surprisingly, the curves associated to work results don’t decline – as one would expect – but decrease even. So, productivity of the remaining staff increased! The most right date in the graph is July 2014 and reflects an organization which has one product team and one support team left. The architecture team disappeared completely, the team is ways lighter equipped with people.

What might we learn? Brooks’ law indicates that adding people to a project doesn’t automatically make the overall project finish faster. It might even end in a longer project run time. We’ve seen that removing people might result in better productivity. We think the fact of removing whole teams dedicated to special topics (in our case: the architecture team) helped to increase productivity in two ways. First, the responsibility of architecture decisions was pushed back into the teams and dead-lock situations where person A waits for a decision from person B just disappeared. Second, the time needed to communicate, agree and disagree simply vanished. Decisions had to be taken and nobody needed to be asked.

Is this a general pattern? I personally think this effect does only appear for a certain period of time. The drawback of such leaner organizations is obviously the lack of work on technical debt and architecture drawbacks. People in such situation focus on the obvious and postpone work on maintenance tasks for later. For me, it is definitely an observation I’d like to share with you. Perhaps you have similar experience? If so, please let me know.

Is there really a relation between the number of staff members and the productivity? Where is the limit? How can one push the limit?

Giancarlo, I think the real reason behind the increased productivity – or the increase in tickets closed (no “political” closing involved 😉 ) is the decrease of discussion and arguing. People were more focussed, less puzzled and were clearer on what to do next.

As I said, I don’t think the observation we made is a general applicable observation – but at least it’s quite interesting to see.

I personally believe, there is a limit to the increase – and after a while it will start decreasing – when business is pulling stories at the same speed they did before. Then the missing staff members will simply lead to too less people to get the job done.

Read you,

Michael.

Thanks for sharing, I like the train of thoughts. I think that it is important to keep observing how teams are performing from different perspectives and how they are affected by changes in the way they organize and in their environment.

As you state, more people doesn’t necessarily lead to more productivity. Fred Brooks wrote that there is an evident communication overhead and there are ramp-up times which have to be considered when adding more members to a team.

Now reducing the number of team members does not generally improve a teams total productivity, unless:

– Removed team members produced disruption to the group or demotivation of other team members (classical example are overpaid underperforming team members who earn more than the rest and produce a tenth). This only improves performance if the reason for removing that underperforming team member was sensibly but clearly communicated.

– Process/Task requires so much communication or steps that each additional team member produces an exponential increase in communication overhead (haven’t seen this).

– Team is excessively oversized – in this case removing one team member cannot have a significant impact.

I’m sure that you have much more data available to analyze what happened and why things changed over time. There may be also other factors which can explain the changes in the numbers you are showing:

– The uncertainty you mentioned was surely keeping motivation low. People were more busy gossiping and trying to figure out what was going on with the company than producing software. Afterwards – regardless of the change in team sizes, stability and tranquility came back to increase productivity.

– In general it is difficult to measure productivity by number of tickets or bugs fixed, as there is a huge variance in the effort related to the associated work. There are also phases where equal items are treated in different ways (like: “political” closing of tickets, bug fixing initiatives, backlog cleanup…).

– Changes in a definition of done – a more “relaxed” goal leads temporarily to a higher throughput.

– I’ve seen developers paralyzed because of the segregation of duties between development and architecture. Technical hierarchies in some constellations create too long feedback cycles for developers: if architects are like a technical police, whenever developers want to do a change or create something new, they feel that they have to consult the guru first – when architects act as advisors (helpers) or coaches, this doesn’t happen.

Keep sharing your ideas!

Regards,

Giancarlo

Wow, those are interesting insights! I think this is correlated to the “everyone is pulling on one string” effect – those who stayed with the company are now really motivated and work well together. Maybe everyone is now better aligned on one common goal or shared vision on what they want to achieve.

Did you consider the impact on product quality (e.g. lead/cycle time for bugs, test coverage) and overall customer satisfaction (e.g. NPS, customer service tickets)?

Nils – thanks for your comment. We didn’t look to much further into the data available – this corelation (is it one?) was so obvious I decided to dedicate a post to it.