Software projects failed a lot in the past. They failed to deliver the value for the business, were too late or ways out of budget. The selected process method was usually the scapegoat for the failure with agile methods being the answer to any question in software development. But as usually in live, it’s not black or white. The selection of the right software process method depends on the surrounding of the project. I gathered some industry input and combined it to reflect the current thinking regarding agile software development methods vs. traditional methods.

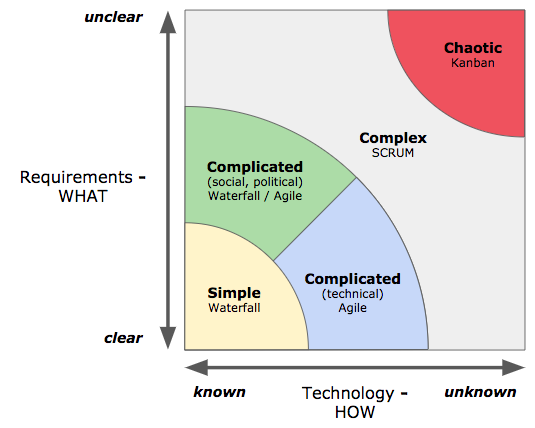

The adapted Stacey matrix

The original stacey matrix supports decision making processes suggesting appropriate management actions and defines four areas: simple, complicated, complex and chaotic. The suggested actions depend heavily on the context of the decision making.

The dimensions of the adapted matrix: HOW and WHAT

The x-axis of the adapted matrix deals with the HOW. If the team knows the technology well and has used it many times before, we’re on the left. Otherwise, if the technology is completely new to the team we’re on the right of the dimension. The y-axis positions the WHAT. On the bottom of the axis, the stakeholder of the project all agree on the goals and have the same understanding of the expected outcome. On top it’s the opposite, no agreed requirements and no alignment on expectations. The individual mix of the project points to a certain area with a process model suggestion in the adapted matrix.

Waterfall …

Waterfall is a traditional project management method with sequential steps and no iterations. Massive upfront planning is done before any implementation work starts. If all goals and steps are clear, waterfall produces consistent results in a predictable and repeatable way. The clearly defined tasks lead to an optimized sequencing and optimal resource allocation. Waterfall optimizes resources and return on invest if cause and effects are clear to anybody in the project team.

… vs. Agile

Agile stands for SCRUM, Kanban and LEAN methods with flexibility, quick response and constantly changing environments in mind. They start quicker with smaller scope for the current increment with the scope being like a rolling window. Uncertainty of the projects’ goals needs quick adjustment and adaptation during the whole execution. Only close and frequent collaboration with all team members make agile projects successful. If causes and effects aren’t clear, agile works in small steps towards a value-generating and broadly accepted result.

Simple = easily knowable, the known knowns

Projects in the simple zone unveil very few surprises, decisions are fact- or evidence-based, advancement occurs in orderly, sequential steps and the WHAT is clear to anybody. Any size projects with clear activities and repeatable results fits in this category. It has been done multiple times before and best practices exist as benchmarks. The process is simple and could be handled in a check-list style.

Going forward in a simple, fully predictable project means reducing it to the maximum to make the single pieces easier to understand. Examples of simple: recipes, tasks on an assembly line, checklist based work.

Complicated = not simple but still knowable, the known unknowns

The complicated zone segments into socially and politically complicated and technically complicated. Complicated means less simple but still somewhat predictable.

In Social/political complicated environments people can not agree on the purpose of the project and the expectation on results is not clear. Requirements are conflicting amongst the diverse stakeholder which could be resolved with waterfall to get clearance on WHY before WHAT before HOW. On the other hand applying agile techniques could help convincing stakeholders to agree on already achieved results and smoothing the further requirements discussion. The project team needs to pay special attention on getting early agreement between stakeholders in place.

In technically complicated contexts it’s clear on WHY and WHAT to achieve. Still, the HOW is not clear. An agile iterative approach helps getting feedback from the project team on the achievements making adaptations possible.

Going forward in a complicated project means as well reducing it to the maximum to make the single pieces easier to understand. Technically complicated is e.g. using a specific technology for the first time. Political/social complicated is e.g. if the relation between cause and effect are not clear enough or conflicting opinions amongst various stakeholder exist.

Complex = not fully knowable but reasonably predictable, the unknown unknowns

The complexity zone stands for high risk and uncertainty and requires a high feedback frequency. Neither requirements nor the execution are clear. Holistic defined process methods don’t work any longer. The context asks for a more explorative approach with transparency, frequent inspection and adaptation. SCRUM as a process method in the toolbox of the agile mindset is the method of choice. It increases transparency with small iterations and frequent check-points allowing cheap adaptations. The team planning is the start point for each new iteration and allows immediate feedback from stakeholders to the teams to adapt the next iteration.

Complexity can not be reduced, some understanding can be achieved and complexity can not be planned, it simply grows. A good example of a complex project is software development in general. The requirements are rarely fully defined right at the beginning and it’s seldom clear which architectural solutions are superior to others.

Chaotic = neither knowable nor predictable, the unknowables

In chaotic zone requirements and execution path are both undefined and the risk is high. Kanban as the most flexible project management method is the tool of choice. With no structure like sprints and the only focus on work in progress (WIP) Kanban focuses on continuous delivering results to allow further modifications in direction and backlog items.

The goal is to move from chaotic towards complex by dividing the problems. The principle “Act, Sense and Respond” helps navigate towards the zone of complexity.

Sources – from where I learned:

- “Agile vs. Waterfall? Don’t Risk Failure By Using the Wrong One” by Terrence Metz

- “The Stacey matrix” by Brenda Zimmerman

- “Simple vs. Complicated vs. Complex vs. Chaotic” by Jurgen Appelo

- “Cynefin framework” – wikipedia

- “Complex? Complicated? But they’re the same, right?” by Sander Huijsen

- “Adaptive Leadership: The Leaders Advantage” by Bill McCollum and Kevin Shea